Design Leaders Who Light the Way

When you’re a Design Leader, solving problems and creating solutions is just what you do. There’s always a new challenge ready to enter your orbit, but even the most experienced creative mind can be caught off guard by problems they didn’t know to watch out for. The universe of design leaders is bright and diverse, and they’ve all got their own stories to share.

We’ve collected our own constellation of thought leaders and design experts working in prominent fields and companies, each one a shining star in their own right.

As William Faulkner said: “Immature artists copy; great artists steal.” Learning from these design leaders won’t just help you grow by light years at a time; you’ll be able to future-proof your own design team by sharing their insights on integrating Design Ops, hiring for diversity, building with collaborative tools, and a realistic understanding of the creative process.

So, go ahead and soak up their knowledge. Why wait around to learn from the rest when you can steal from the best?

Creating Diverse Teams with Samantha Berg

Chime is a financial technology company aimed at making banking accessible to everyone. The company's Head of Design from 2019 to 2023, Samantha Berg has been successfully leading design teams for 15 years and won the 2021 Moxie Award for her outsized contributions to the tech industry.

While design has always been her passion, she’s also become a devoted advocate for equity in the workplace.

Berg shared how she leverages diverse educations, backgrounds, thoughts, and identities to create a design team equipped to tackle a wide range of user problems.

"We’re not always the people we're making things for."

Defining Diversity and Why We Need It

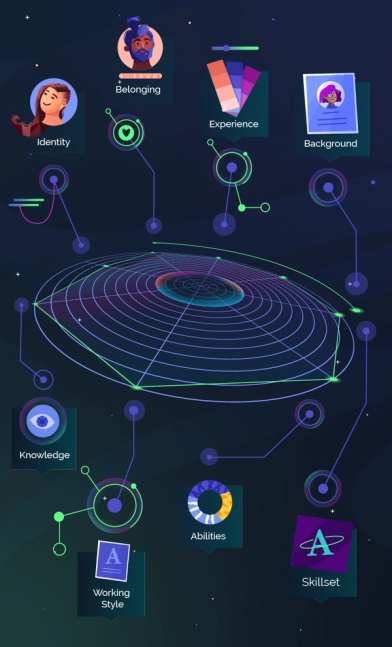

Berg defines the four aspects of diversity as follows:

Identity and Belonging. This covers race, gender, sexuality, income, education access, religion, citizenship, and age.

Experience and Background. This is everything that informs the point of view the designer has, including upbringing, schooling, and past jobs.

Skill Sets and Knowledge. This is the diversity in specialty and tools a designer brings, such as interaction design, visual design, motion design, content design, research, etc.

Abilities and Working Styles. This is the diversity that recognizes that not everyone works the same way, including introversion and extroversion, being an early bird or night owl, neurodivergence, disabilities and impairments, etc.

Inclusive design requires a wide array of identities, backgrounds, abilities, mindsets and experiences that reflect your current customers and prospects.

For example, Chime’s banking service is used by people from all backgrounds, ages, and income levels. With 61% of America living paycheck to paycheck, it follows that a majority of Chime’s users may be struggling financially. If no one on the design team has ever known the stresses and lifestyle of a lower-income household, it may be more difficult to understand (and thus provide solutions for) a large portion of their customer base. There is, of course, in-depth customer research to help fill in gaps, but having a wide range of people who share the same background with customers can bring a whole new level of inherent empathy and understanding to your team.

In essence, a lack of diversity in Berg’s four categories can hurt the people they've been trying to help.

The classic example of this IRL is the design of crash test dummies. A team of male engineers created the crash test dummy based on their bodies and experiences. Car safety features were then built around the data obtained from this average male dummy, ignoring the differences in male and female bodies, including temporary disabilities common to women, such as pregnancy, which cause physical changes to the body. As a result, women experience higher injury and death rates during crashes

Eventually, this issue was resolved, and modern cars are now much safer for women, but it's easy to see why having a woman on the team could have saved lives.

While lives likely don’t hinge on your design team’s work, the success of your projects might. Having a diverse team not only keeps you from alienating customers, it helps you find and solve problems you didn’t know existed for entire subsets of the population.

How To Hire and Run a Diverse Team

Berg uses a spider diagram to assess how diverse her current team is along the different diversity axes: identity, belonging, experience, background, skill sets, knowledge, ability, and working style.

Then, she uses the dips in the spider diagram to see what the team may be missing. From there, she moves to interviews and potentially hiring—without looking for “culture fit.”

“Hiring for culture fit assumes your work culture is perfect.”

Culture fit and diversity are counterproductive to each other. You can’t have a homogenous culture that never changes and is somehow full of new ideas. Embrace culture change, or as some say, “culture add.”

That said, it’s not just about hiring. The pathway to attracting diversity and then quickly losing it is to not support the diverse needs of diverse people.

To support diversity in identity and belonging, work with your people and HR to adjust your processes for unconscious bias. This includes developing educational programs on racism, sexism, agism, homophobia, and other forms of conscious and unconscious discrimination through seminars and workshops. It includes ensuring feedback comes from an equal number of men and women, and making sure when in performance reviews, you talk to everyone’s accomplishments rather than their personal characteristics. It means regularly reviewing salaries and compensation for equity, and putting policies in place to protect people suffering from discrimination and harassment.

To support diversity in experience and background, don’t be afraid to hire people who don’t fit the usual requirements. If a portfolio is good enough, a lack of formal education shouldn’t prevent hiring. It also means looking harder for the “diamond in the rough”. A lack of formal education or big names on the resume can cause promising candidates to slip through the cracks or be passed on in searches in favor of the “usual” candidates. Seek out communities representing underserved groups and source from places other than LinkedIn.

To support diversity in skill sets and knowledge, hire designers from different fields and proficiencies to round out your team. Don’t be afraid to play with adding some specialists to your team, especially in the worlds of content, prototyping, and motion, rather than continuing to hire generalists.

To support diversity in abilities and working styles, consider the team’s work habits, needs, and hours of productivity when scheduling meetings. Are your meetings asking more of folks with learning disabilities, motor impairments, or neurodivergence? For introverts, a high number of meetings are draining. For someone with autism, intermittent meetings may make it harder to find extended focus and get work done. For those with anxiety, a meeting later in the day can hang over their head and destroy their productivity. With time zone differences, try to rotate meeting times so no time zone is favored (or inconvenienced) too often.

Inside the Design Process

While many companies have Design teams and work closely with Design, not all of a company’s employees truly understand how design works. Berg has designed sessions that fit into a company’s employee onboarding to show that Design isn’t just an artform, it’s a scientifically backed process.

At a company that requires more Design education, Berg’s team hosts an interactive session to show employees exactly how the team formulates design solutions. This has the secondary effect of showing off your design team’s genius.

In these sessions, Berg or her team walk employees through a problem-solving exercise. Let’s say a client, or a product team, comes to them and wants to build a bridge from San Francisco to Oakland. She’ll pause and dig into why they need a bridge - and invite the employees in the sessions to do so with her.

She asks them: “Why does it have to be a bridge?” She and her team encourage the employees to start talking about the problems they’re trying to solve, rather than the solution. As they brainstorm problems to solve, the group starts to consider other solutions for moving people from San Francisco to Oakland.

They might suggest a helicopter, and talk through its merits and flaws. You don’t have to spend time building helicopters, you can buy them and move people right now, and helicopters can move people quickly. But, helicopters don’t carry many people, they have maintenance and fuel costs.

Or they might suggest a ferry, which is cheaper and faster to implement than a bridge, carries more people and equipment than a helicopter, but is extremely slow.

In essence, Berg and her team use this onboarding meeting to help employees focus on problems they want to solve, rather than solutions they want to make pretty. Berg and her team will then provide solutions—which is the root of why companies hire design teams in the first place.

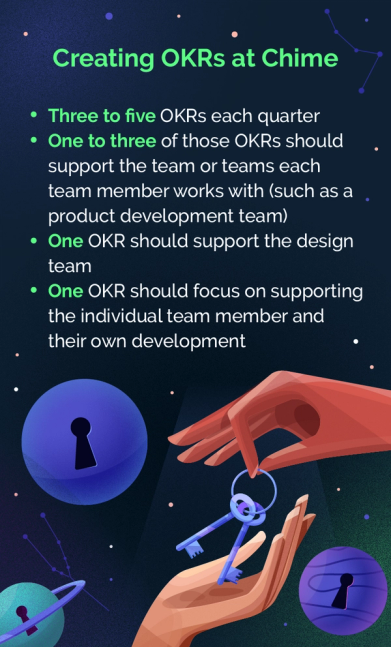

Creating OKRs at Chime

Berg shared with us her strategy on Objectives and Key Results (OKRs), and how she uses them to develop herself and her team members. Here is what she recommends:

These OKRs, split into categories, help Berg, her team, and the company ensure everyone is growing. The designer is working on their design skills, the design team is improving and, as a result, the company is growing.

Takeaways and Further Reading

Berg’s philosophy on diverse teams breaks down into a few major ideas:

- Diversity isn’t just race and gender—it encompasses background, education, experience, skillset, health, and income.

- Diverse design teams can solve more problems and reach a wider audience.

- Diversity isn’t enough—to achieve equity and retain diverse talent, you have to employ policies to support everyone uniquely.

- Teach people what your design team actually does and how it works by showing them the process.

- Create development goals that help the design team, the greater company, and the individual.

To learn more about Samantha Berg, check out:

- Her interview on “Becoming the Head of Design”

- Her video on “Building a Multidisciplinary Design Team”

- Her website

- Her instagram

- The episode of the Design MBA podcast starring Samantha Berg

Turning Task Takers into Strategists with Shachar Aylon

Shachar Aylon is a creative visionary and recently the Executive Creative Director of Picsart from 2020 to 2022, a photo and video editing design platform. He's a photographer, writer, designer, and creative leader who’s been recognized by Ad Age as a “Creative to Watch” and for his team’s design project “Unboring Boring.”

Aylon shared his take on design leadership, creativity, and the structure of his team at Picsart.

To Aylon, design teams have to bring strategic thinking into every aspect of their creative work. A design can be beautiful and compelling, but without knowing what it’s trying to accomplish, it’s hard to evaluate the end result.

“The worst thing is to present a beautiful project and leadership says ‘why the hell did we make that?’ That’s a waste of time.”

How the Design Team Fits Into Picsart

While working at Picsart, Aylon was tasked with handling everything related to branding and creative work, from email marketing to brand awareness campaigns.

Since Picsart aims to make design more accessible to everyone, the company puts a big emphasis on their own design capabilities. Across the entire company there are almost 100 designers, split into three different departments:

Bucket #1: Product Design. In charge of designing the user experience and overall look for each product. From small buttons, to reimagining how picture editing should be done on touch screens, the team is in charge of it all.

Bucket #2: Content. The tools and resources Picsart provides creators. This includes brushes, stickers, templates, and filters for creators, small businesses, and entrepreneurs.

Bucket #3: Brand and Creative. This team is focused on design and campaigns for marketing and engagement. They help define messaging, visual guidelines, and go-to-market plans for various channels and products.

The Brand and Creative team has over 30 people and sits within the marketing department. This team includes producers, writers, art directors, motion designers, and copywriters, all working closely with Strategy and Marketing Communications.

These 30 designers are spread across eight countries. Because the team is global, Aylon was always pushing the importance of clear communication. This means embracing asynchronous communication and being conscious of how meeting times can exclude different time zones.

He is also a strong believer that in order to unlock the creative potential of each team member, designers need to be given leeway to work in their own way.

His approach to working styles is:

“As long as we clearly articulate what success looks like, there is freedom within every project to approach challenges in unique ways. Every person has their own working style and a different approach to creative problem solving.”

Unlocking creative potential requires deep work. So, when the creative team at Picsart is over capacity and design requests keep piling up, instead of distracting their designers, they turn to Superside to fill the gaps. Superside gives Picsart an always-on, dedicated design team that plugs into any process to access speed and uncommon capabilities (e.g., motion graphics, illustrations) using a design platform built for briefs, feedback, and collaboration.

When Aylon needed social media ad variations, he used Superside to scale with the increased demand.

Creativity Needs Variety to Survive and Thrive

Aylon believes his team—and all creatives—need to experience new challenges to get inspired, grow, and stave off creative burnout.

So, Aylon sometimes assigns tasks not just to the best designer, but to the person who could benefit most from the work. The person who could learn from it and grow by overcoming it, especially a junior designer.

“Maybe they’ve never touched motion before and want to get their hands dirty. Let them experiment, let them try.” - Shachar Aylon

This not only gives designers the chance to learn something new and be refreshed by the novel challenge, but it also builds trust between them and their manager. There’s an implicit trust there, when the designer realizes that their manager trusts their ability to figure out a new skill or creative angle.

The designer knows a senior or more skilled team member could have been given the task, but their leader trusts them and is invested enough in their growth to put the project in their hands.

Of course, not every task should be distributed this way, but tasks with large lead times or low impact make for great education projects.

Promoting Productivity and Strategy on the Team

Aylon embraces the “work smarter, not harder” philosophy for his team, suggesting that effective productivity comes from precise design strategy.

After all, what is a strategy but an attempt to lower the likelihood of wasted effort?

Aylon argues that the “high risk, high reward” Superbowl ad style of marketing and design does not fit every company. Instead of dropping a million dollars on a TV spot that took seven months to make and hoping for the best, some smaller companies can try to prototype ads on social media or smaller streaming TV platforms, and further develop the one that performs best.

For example, the goal of Picsart’s “Unboring” billboard campaign aimed to show how any image can be turned into something remarkable. To drive the point home they decided to “never let a viewer encounter the same image twice,” using a bank of high performing brand images that were tested on digital platforms.

And that subsequent data is useful not only for the “Unboring Project,” but also for any other ads they need to design in the future.

Clients and stakeholders find this approach less stressful as well. Rather than betting all their money on one horse, they get to spread their investment over multiple thoroughbreds creating more opportunities for success at a lower cost.

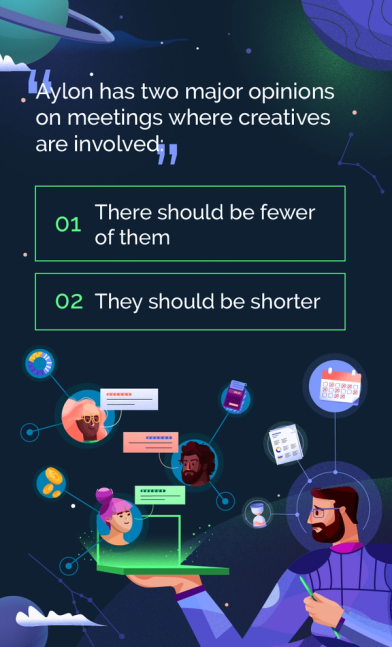

Design work begins after the meeting ends

At the beginning of a large design project, Aylon recommends setting up a briefing so the creative team understands what they are trying to accomplish and allow for any outstanding questions. Regular syncs are important, but not every team member needs to attend those. Usually the subjects being discussed are relevant to managers or key stakeholders, who can later relay the information to the rest.

Put simply, as opposed to a lot of other disciplines where decision making happens within the meeting, for designers the bulk of the work happens after or before the meeting. It’s the job of managers to summarize action points, and allow their teams to focus on what they do best - being creative.

“I’ve been in hour-long meetings where what the designer needed to hear took up 10 minutes.” - Shachar Aylon

Aylon also suggests keeping raw data out of design meetings. Instead, design meetings should go over the insights obtained from data rather than the data itself. Of X, Y, and Z, Y did best. Done. More often than not, the actual percentages or number of clicks doesn’t really matter to a designer—what matters is the knowledge gained from the data. Which idea performs best, and why? What can we learn from it? That’s what the design team should be talking about.

Designers are creatives, and while it might be a cliche, it isn’t any less true: meetings and presentations filled with raw numbers put creatives to sleep. And, most damningly, wastes their time. This is why it's important to dissect the data and use it to influence creative decisions. Numbers on a screen will only go so far.

Takeaways and Further Reading

Shachar’s design leadership style has a few unique tactics:

- Don’t be afraid to occasionally give low-impact projects to the designers who would benefit most from them, even if they’re not the most senior

- A focus on strategy increases effective productivity

- Trial and error works better than big unproven leaps for smaller design projects

- Meetings for creatives should be more about insights than data/numbers

To learn more about—or from—Shachar, check out:

- Shachar's artistic website

- His video on “Balancing Process and Exploration on a Design Team”

- His Youtube channel

- The Domestika Curious Minds podcast episode “Beauty is in the Eye of the Retoucher”

- The amazing art project he helped create, “405 Nanometers”

Designing in a Remote World with Vuokko Aro

Vuokko Aro is the VP of Design at Monzo, an international financial app that streamlines online banking without fees. She’s a UI, UX, and interaction designer with a special focus on mobile platforms.

Aro shared her team’s structure, her leadership philosophy, and how design teams can not only just adapt to remote work, but also thrive with the right structure and communication techniques.

“In remote design, we’re all the same size rectangle on the screen.”

Monzo’s Team Structure and Toolstack

Aro leads Monzo’s design department, which includes user research, product design, and brand design.

A typical day in the life for Aro as VP of Design involves 1-on-1s with designers and cross-functional stakeholders, whiteboarding and design jams, conversations with C-Suite, and coaching sessions with her team.

Her coaching sessions aren’t about offering tons of advice or micromanaging. Instead, she finds the most effective form of coaching is allowing herself to be a sounding board for her team members, and providing additional context or perspectives to help explore topics and find inspiration. Often, having a team member share their problems out loud is enough to inspire them to find new solutions.

This method of problem-solving is backed by science, too: turns out your brain actually works better when you talk.

"Design is in a unique position to make ideas tangible, and to then lead a discussion on whether the direction is right or not. After that we go back and forth, working our way towards the correct solution together," says Vuokko

Monzo doesn’t have a dedicated Design Ops person or team, so much of those responsibilities are spread across multiple team members. It just so happens that, as the VP of Design, many of these design ops responsibilities fall onto her plate.

“I’ve taken on probably too many of those Design Ops functions,” she admitted. She also shared that Monzo is hiring (at the time of this interview) a Research Ops person to coordinate their extensive research operations.

For team size, Aro likes to keep her’s as lean as possible. Human-centered design plays a big role in leading product at Monzo, so it’s important for each designer to own a meaningful slice of the user experience. Career development is also easier with large opportunities for each designer to grow into. At the moment, they’ve hit just over 25 people but are expanding quite rapidly.

Her primary concern has been that her design team should be “good citizens,” working together with a sense of camaraderie and learning from each other. She finds this deep collaboration and coordination is possible but takes more work off as teams get larger.

Aro shared Monzo’s toolstack, all which she considers essential to the team’s daily operations.

- Figma - The design collaboration tool for vector graphics and prototyping

- Figjam - An online whiteboarding tool for meetings and design jams

- Slack - Used for team and partner communication

- Google Workplace - Gmail, Google Docs, and Google Drive

- Protopie - A virtual no-code prototyping tool for testing and demonstration

- Notion - An internal documentation platform. Aro’s team made a full design log in Notion after the pandemic that they use every day now.

- Adobe Suite - Specifically Adobe Illustrator and Adobe After Effects for design and editing.

She praised Figma in particular, which she found especially useful once the pandemic moved most of the team’s work to long-distance collaboration.

Overcoming the Challenges of Remote Design Work

Aro’s team were forced to go fully remote during the early pandemic but found that there were advantages to remote design that are worth considering before returning to shuffling everyone back into the office.

The advantages of a remote design team:

- First, the challenges of remote work forced Monzo to rethink how they design and collaborate. As mentioned earlier, Figma and Figjam rose to prominence in their tool stack, as did Notion through the team’s design log for documentation.

- Second, Aro’s team found this remote collaboration in some ways superior to in-person design jams. Everyone is at their own workspace with an HD screen and access to the entire digital whiteboard, a sharp contrast to staring at a screen across a room or fighting for dry erase pens. There are team members, especially introverts and those who prefer more quiet time, who are benefitting from the switch to remote work.

“In-person, some people might be more comfortable being quiet and disappearing in a room.”

Depending on the company policies, remote work can also lead to a larger talent pool. Instead of only hiring designers in one location (like London, San Francisco, or Toronto), you now have access to creatives from around the globe. This is exactly what we do at Superside, with 650 employees in 70+ countries.

She also credited the text chat sidebar on the side of a video calls for enabling useful side conversations that everyone can still access. That dialogue can be seen by the entire team, where it would have been lost in the office or physical space. It allows team members to spin off with an idea and discuss it without bringing the entire meeting to a stop, or losing the idea completely.

Then, team members who might have been talking on video can actually catch up on the conversation they might have missed.

Now that pandemic restrictions are easing, the Monzo team still works remotely, with the option to go to the office if and when they like.

Aro found that a few people––2 or 3 designers of their 25––can be found in the office on any given day. They’re the folks who miss the interaction and the ability to collaborate socially: extroverts, in other words.

During the full-remote era, and even now that remote is an option, the team still does online social events to promote interaction and help with bonding. They’ve participated in at-home scavenger hunts, and worked on art projects together. Everyone might get the same kit to put together, or a chunk of clay to do pottery over video chat

Other times, they have the “virtual happy hours” that have typified pandemic-era work socialization, drinking together and talking about anything but work.

The team has also started doing quarterly in-person Design Team Days where everyone travels to the office or another location for a day of workshops and fun together. These infrequent but recurring social gatherings have helped strengthen bonds in new, different ways.

The Unique Problems of Interaction Design

Aro specializes in UI, UX, and interaction design. She likened the difference between static design and interaction design to the difference between movies and video games.

Movies are enjoyed passively, and their creativity and design can affect you strongly, but interaction design is more like making a video game. Every interaction must tell a story. Every swipe or tap in a mobile app needs to mean something and provide feedback through motion, visual details, haptic feedback, or even sound.

In her team, Aro stresses the importance of creativity and delightful human touches through interaction design. Apple’s “Weather App” is one of her paragon examples: the way water bounces off elements of the UI when it’s actually raining outside. “What would it take for this to feel magical?” she asks her team.

For design leaders, she recommends moving away from minimalism and flat, samey design. There are only so many combinations of color, silhouette, and basic shape before everyone’s logo or icon looks exactly like everyone else’s.

Joy, fun, and expression must be the pillars of interaction design on a creative team. Though, in her opinion, form should still follow function.

“If I have to choose function over form, I choose function. Something ugly can actually be beautiful if it’s improving people’s lives.”

Takeaways and Further Reading

During her time as a design leader, and through the challenges of the pandemic, Aro discovered:

- Remote collaboration software makes design sessions more accessible and interactive for all types of team members

- DesignOps and ResearchOps become vital as teams grow larger

- Quieter team members have the opportunity to shine in remote design and communication

- Andy Work’s “No More Boring Apps” philosophy to help designers inspire this rejection of lifeless design aesthetics

To learn more about Vuokko Aro, check out:

- Aro’s 2021 interview with Canvas Conference

- Aro’s 2018 interview with Marvel

- Her twitter feed

- Her staff Q&A session at Monzo’s Community Forum

- Aro’s 2021 talk, “Case Studies from Scaling Monzo”

- Aro’s FDS 2019 talk, “Growing World Class Design Teams”

- Aro’s speech at Interact London, “Building a New Kind of Ban

Creative Leadership Models with Adam Morgan

Adam Morgan is currently the Senior Director of Brand and Creative at Splunk. Formerly, he was the Executive Creative Director at Adobe, one of the most well-known software companies in the world. Adam’s been in design and leadership for 25 years, and is the author of “Sorry Spock, Emotion Drives Business.” He’s also the host of the podcast “Real Creative Leadership,” where he uses his passion and understanding of creative leadership to help creatives around the world.

Morgan shared how creative teams need to have ownership of their client, their work, and their audience. Creative leaders must foster that responsibility and teach “creative types” that they can be business-oriented as well.

“Creative people have an opportunity to step up and lead. Take ownership of creative strategy and lead with other divisions or clients. Don’t hide behind an account person or project manager but be the face of trusted creativity.”

The Creative Team Structure at Adobe

During his time at Adobe, Morgan’s division was split into five areas—video, web, content, demand, and studio management—with the creative directors of each division reporting to him.

How Communication and Collaboration Happens

Morgan’s teams at Adobe broke communication into different channels, primarily by speed and purpose of communication. For fast, short communication, they used Slack.

Each Slack channel served different divisions and purposes—one for leaders, one for each department, one for the whole studio, and so on. For rapid communication, day-to-day updates, and personal chats—Slack was Adobe’s venue of choice.

For major project communication and collaboration, Adam and his teams used Workfront. Workfront (which Adobe recently acquired) is an enterprise project management software that’s used for all project communication and collaboration.

That emphasis on collaboration carries over to how the creative department at Adobe handled their wide array of meetings, while still staying completely remote.

- Half-hour watercooler meetings to chat and blow off steam

- A weekly creative meeting with each team

- A creative workshop every Friday morning to get everyone inspired

- Purpose-driven town hall meetings for big announcements and updates

- Business meetings for clients and financial work

- Leadership meetings with division heads

All these forms of communication enabled Adobe's designers to lead their projects/work autonomously which fostered better innovation.

Designers Can’t Innovate Without Ownership

For example: When putting a team member in charge of emails for a client, it isn’t enough to hand off the work and have them do it robotically. Instead, Morgan encourages innovative thought and the freedom to push the limits of their responsibility. He does this by peppering them with questions that will expand what they think they can do:

“How are they pushing email for this company? How much animation should be in there? How straightforward should email be? What are the best practices, the newest trends?” - Adam Morgan

As the leader, he’ll always provide guidance, but the intent of this pushing is to prevent stagnation or “good enough” thinking. Team members can’t just be taking orders and pumping out work. They aren’t just a set of hands, they should be problem solvers that understand the business.

Instead of stepping in to solve their problems for them, he steps back and empowers them to solve it for themselves.

This approach allows them to become an expert on that topic (like email strategy) in their own right, and will allow the team member to spot problems before they need solving in the future.

In essence, make your team members experts and give them the onus and the power to make things better.

Everything else is just micromanaging.

Morgan’s Models for Creative Work

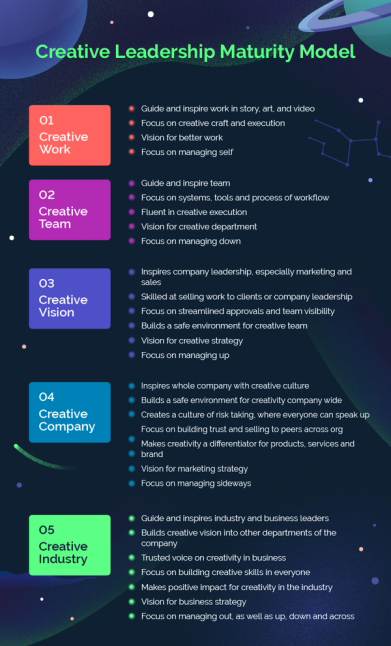

Morgan created a few easy-to-understand visual models for his philosophy on leadership and creative work: the Creative Leadership Maturity Model, and the WHELM scale.

In the Creative Maturity Model, creative growth is split into five ascending sections, each representing a larger sphere of creative influence.

The 1st column, Creative Work, represents the self––once you’ve become competent with creative work and managing yourself, you’ll be ready to move to column 2, the Creative Team.

The 2nd column, Creative Team, means you’re ready for team leadership, inspiring others and developing systems to improve workflow for others.

The 3rd column, Creative Vision, represents someone who has achieved competency at team leadership and is learning how to innovate rather than iterate, and how to communicate their team’s value to stakeholders.

The 4th column, Creative Company, is for the creative leader who is working on the level of company culture, trust, and strategy.

The 5th column, Creative Industry, is the final level of creative maturity, and represents leaders who are ready to influence the greater industry beyond your company. This is the level for visionaries, taste makers, and true influencers whose voice echoes throughout their field.

These aren’t just checklists for success, though they are useful for that purpose. These columns can help leaders figure out next where they are, what they know, and the competencies they need to develop to move to the next level of their career.

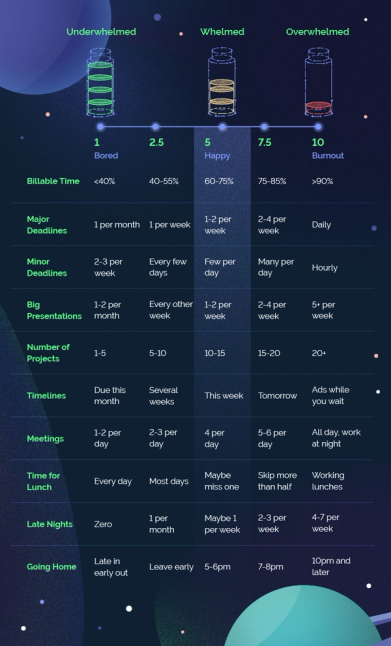

Morgan’s WHELM scale helps creative leaders assign a fair workload for their creative team.

In his example, which can be examined in more depth in the link above, Morgan created a WHELM scale for an ad agency.

The WHELM scale will look different for each company and team, but the idea is that you create a scale from 1 to 10.

1 is “Underwhelmed” with work, 5 is “Whelmed” or relatively content with the workload, and 10 is “Overwhelmed” and ready to burn out.

Then, below the scale is each category of work relevant to your team. It may be deadlines, number of meetings, reports to create, overtime, presentations, etc. Then, you determine (through team feedback and observation) a reasonable workload.

Morgan stresses that the point here isn’t to level out all the numbers: instead, the team member or manager uses the scale to figure out balance. If a team member is at a 9 on projects but a 2 on meetings, that’s probably okay, at least in the short term.

The WHELM scale visualizes your team’s workload in realistic ways, helps each team member understand their own level of stress, so that you can tweak and balance the “sliders” to keep boredom and burnout at bay.

Takeaways and Further Reading

Morgan ran his team at Adobe with a few strategic pillars:

- The bigger the team, the more structure and communication delineation you need

- Designers need ownership to grow and innovate

- Creativity doesn’t have to be a soft science—we can use detailed models to grow ourselves and our team

To learn more from Adam Morgan, check out:

- His professional website

- The Adobe blog, where he frequently writes articles about Adobe and creative leadership

- Adam’s podcast, “Real Creative Leadership”

- Adam’s talk on making the jump to creative director

- His book on the science of creativity in business, “Sorry Spock, Emotions Rule Business”

Fighting Burnout and Inspiring Creativity with Ching Hsieh

Ching Hsieh is the Sr. Staff Product Designer, previously Director of Product Design at Included Health, an inclusive healthcare platform that integrates insurance, medical care, and health information into one easy-to-use point of access. Hsieh has been in product design for over 10 years, with a focus on UI, UX, and IxD in the medtech field.

Hsieh believes that creative leaders must help designers find inspiration and fight burnout in difficult times by giving them purpose, time, and leading by example.

She also believes that management shouldn’t be the only path to design leadership. More on that below.

“The most challenging aspect of being a design leader right now is holding up that torch of hope in dark times.”

The Design Team Structure at Included Health

The design team at Included Health is embedded, meaning instead of a separate design team working on all projects the company needs, they have designers dedicated to various functions within the company.

The designer on each of Included Health’s service lines include: virtual primary care, virtual behavioral health, health navigation, foundational member experiences, care platform, and more. These designers are embedded with the product and engineering team of each service line, and attend all kick-offs and project meetings to build rapport and expertise on their assigned topic.

And, of course, the designers work side-by-side with their team on the current project they’re tackling.

Hsieh raves about Figma’s collaboration and design software. Unsurprisingly, it’s her and Included Health’s design tool of choice.

“We're on Figma during the work day, all day, every day.” - Ching Hsieh

Not only do they enjoy the collaboration features, Figma condenses many of the other tools Hsieh and her team were using to design interactions, prototype, test, and make presentations.

Hsieh and her team particularly appreciate that Figma is a cloud platform providing a single source of truth. They can open the same file, work together, and see everyone’s cursor and gestures all in a remote environment. Plus, version history allows designers to roll back changes whenever they need.

However, despite her and her team’s appreciation for Figma, she does suggest that there’s always room for analog.

“Tools like Figma make designing pretty easy, the way smartphones make taking photographs easy, but does that make everyone a good designer, a good photographer?”

Hsieh instead advocates for a rough pencil sketch instead of a highly polished and ready-to-present visual design, especially during the early phases of ideation. She’s found that the lo-fi nature of a simple sketch encourages discussion, new ideas, and the freedom to go in new directions without the added pressure of messing up something pretty.

Flash and color are important for design, of course, but they can distract the team from the actual problems they’re trying to solve for their users.

Hsieh’s Five Hires for Every Design Team

When Hsieh first joined Included Health, they only had one designer. She had to hire 6 more designers in 6 months to create the team she needed. This was a significant learning experience for her, which helped her formulate a sort of “ideal team” she now shares with other design leaders looking for team-building advice.

These are the first five hires Ching recommends making on a scale-up design team:

- Hsieh’s First Hire: A generalist designer who can do ideation, research, visual design, and product shipping.

- The Second Hire: A visual design specialist to help uphold quality design on the team, to lead by example by showing the team crisp, polished designs.

- The Third Hire: An interaction designer with expertise in prototyping. Someone who can create a real thing that can be tested, who can work with engineers and even talk to stakeholders. Here, someone with a project management background is a plus.

- The Fourth Hire: A research specialist, with strong interest and experience in the field. Their job is to make sure the design team is always getting the perspective of the customer and testing the team’s designs against real data.

- The Fifth Hire: Hsieh calls this “the wild card” hire, and is essentially her “free space” after hiring everyone else. This slot is for balancing out the existing team, for a designer who can cover either the current gaps in the team or for design expertise that might be specific to your actual product.

And when hiring is tough, or budget doesn't allow for more headcount, Superside is there to help teams scale their creative output in a much more flexible and sustainable way. Which is exactly why the design team at Included Health uses Superside!

Fighting Burnout by Doing Less

Creativity, productivity, and burnout go together like rainy days, PJs and a cup of tea. It’s just part of the natural order. While it can’t be eliminated entirely, Hsieh has found there are far better ways to tackle the issue.

To Hsieh, one of the problems with how we tackle burnout in the corporate world is that the most popular methods tend to make the situation worse. These “solutions” to burnout are all tasks: meditation, exercise, company retreats, team games. They require energy, they take time away from team members, and they all come with physical, social, or mental burdens.

These methods are all designed to “fix” you, to make you better. But that’s just productivity in a mask.

“Why do we have to do something ‘productive’ to fix burnout?” - Ching Hsieh

The free time is more important than another Zoom social hour because everyone’s stress relief is different. What frazzles one team member may energize another. We can’t be the fun police.

Team members need to hear that work is less of a priority than their physical and mental health, and be given leeway to handle it their way.

“Two+ years into the pandemic, we've gone through cycles of hopelessness and burn out. As a leader, people look to you for hope.” - Ching Hsieh

Leaders have to inspire their team when they’re often flirting with burnout themselves. Hsieh shared with us that while the solution isn’t easy, it’s simple: you have to show up for your team and keep empowering them. You don’t need energy to give energy, and sometimes helping others can recharge yourself.

She also brought up a point that challenges pre-pandemic ideas of team building: being present for your team members is a little more manageable over video chat.

In video chat, you’re just a window on your team’s monitor, you’re not physically present. And your time at the window is short—it’s not like Zoom calls last all day (in theory). In an office, a burned-out design leader might have to perform for eight hours a day every day.

With video meetings, a struggling leader only has to keep the beacon of inspiration for 45 minutes to an hour at a time. That’s far less energy expended, and more breaks in between to allow leaders to center themselves—particularly important for introverted leaders such as Hsieh.

Her other suggestions for burned-out leaders was to give themselves the same time and consideration they’d give their subordinates.

“Take a walk, walk the dogs. Close the laptop at the end of the day and keep it closed. You have to balance yourself.” - Ching Hsieh

The Shift from Team Lead to IC

Balance isn’t binary. It’s about weighing your options.

"Success is too often defined singularly. In the design world, you’re either on the management track, or you’re on the IC track. While these two paths are positioned as 'dual' or 'parallel' tracks, the reality is that as an IC designer, there comes a time when you are nearing the top rung, and you look up — do you keep climbing onto that management ladder (which is actually stacked on top of the IC one)? Or do you stay where you are, and realize that there’s nowhere else to go?"

For Hsieh, after returning from maternity leave to a company that had undergone a merger, operating with new team members she didn’t know, and who were using a different set of tools from what she had implemented—the role no longer seemed to fit. She made the monumental decision to leave leadership and transition to an individual contributor (IC) at Included Health—more in line with her passion for designing and newfound family life.

“Suddenly, my old role at work felt like an itchy, oversized sweater, in which I felt small and uncomfortable in.”

For her, burnout didn’t come from overwork, but a natural result of life circumstances. Burnout manifests in many ways such as creative blocks, health concerns, or, yes, just a massive workload.

To avoid burnout, the design team at Included Health uses Superside when they’re stuck in cycles of hopelessness or need some inspiration. Superside gives them a dedicated team that knows their brand, so they can spin up fresh ideas quickly, and pump out design variations at scale, buying back time and energy for their own projects.

As for Hsieh, she's found her groove again now as an IC at Included Health. She's still there supporting her team, working right along side them!

Hsieh’s message to any design leader who finds themself missing the craft, idly itching to switch courses but not sure how:

Takeaways and Further Reading

The design team at Internal Health thrives during difficult times with a few key tactics:

- Embedded designers gain expertise and build relationships in their field

- Burnout is endemic for team members and leaders, and they need to be given the time to decompress in their own way

- Scaling design with external help can lighten the workloads that lead to burnout

To learn more about Ching Hsieh, check out:

- Her LinkedIn profile

- Her insightful Medium article about quitting social media

- The TIME article naming Caption AI, a product she and her team built during her time at Caption Health, as one of the 100 Best Inventions of 2021

- Hsieh’s Twitter feed

Build Your Vision, Borrow Their Experience

The design team of the future needs creative leaders with vision. It needs leaders who understand how creativity works, how to smooth design work with experience, and how to build, support, and inspire design teams.

Samantha Berg at Chime highlighted the power of a diverse design team, and how it allows us to connect with an equally diverse audience.

“To design for any background, education level, and ability, we need a design team that reflects that experience.”

Shachar Aylon, previously at Picsart pushed the importance of variety to creatives, and how learning new skills helps team members grow by pushing them in exciting new directions.

“I try to get everyone on different and interesting projects. You have to give creative people new challenges and tasks. Let them explore the boundaries of creativity.”

Vuokko Aro at Monzo discovered that remote design tools and communication create an equal, interactive environment that helps team members find their voice.

“In-person, at a conference table, these people might be more comfortable being quiet and disappearing. And we lose their unique input.”

Adam Morgan at Adobe shared how team members need power and freedom to go along with their duties, and how to model creative growth.

“Designers can’t have responsibility without ownership. They need to own their work and run with it.”

Ching Hsieh at Included Health explained how leaders can help designers deal with creative burnout by giving them their time back, and that leaders need to give themselves the same leeway they give their team.

“Everyone’s way to decompress is different. I think the most powerful thing you can do is give your people the gift of time.”

While no two design teams are ever going to be 100% alike, the wisdom to be gleaned from successful design leaders can point leaders in the right direction and even inspire them to find new leadership models.